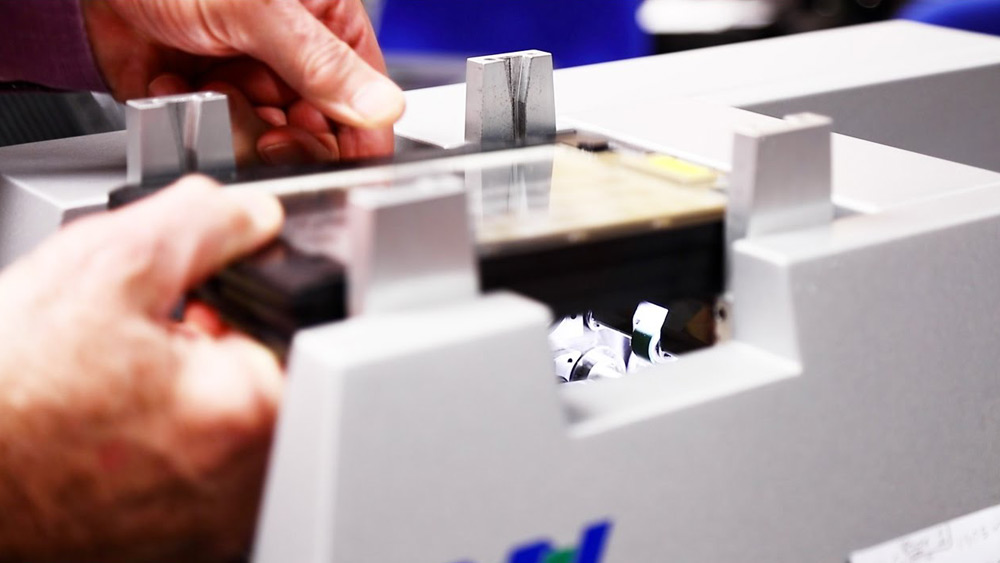

There are huge quantities of microfilm material in the archives of organisations and institutions in…

Digital records ‘obscure the past’

The pace of technology is such that what was deemed cutting edge 15 years ago is generally considered obsolete today.

Works like the Gutenberg Bible can still be read

Digital technology could result in the loss of priceless historical records,

explains Tad Piesakowski.

For households this has been evident in the steady migration from analogue to digital: vinyl gave way to CDs, audio cassettes to minidisks and video tapes to DVDs.

The television industry is facing similar problems with an ongoing project to transfer its archive footage from obsolete videotape to current tape formats or even digitised.

When planning Project Gutenberg, the internet archive of free electronic books, its architect, Michael Hart, recognised the problem.

He warned: “Alice in Wonderland, the Bible, Shakespeare, the Koran and many others will be with us as long as civilisation.

“An operating system, a program, a mark-up system will not.”

Consequently he specifies the use of simple ASCII code to archive books and documents because “it is the only text mode that is easy on both the eyes and the computer.”

Indecipherable archive

An example of the problem is the Digital Domesday Project.

Domesday Book of 1086 is in fine condition

The original Domesday Book was written 925 years ago and is, for those who can read Latin, still perfectly legible.

Its intended digital successor, somewhat newer at 16 years old was, until this week, largely indecipherable.

This was not because the data had deteriorated, but the format chosen to record it had long been abandoned and so consequently devices to read it had disappeared as well.

Last month, this issue of digital versus traditional archiving came to the fore in the UK Parliament.

As part of its continuing plans to modernise Westminster, the government put forward a proposal to end the centuries-old tradition of recording Acts of Parliament on vellum, commonly known as parchment.

Appropriate parchment

The plan was to replace them with CDs and archival paper. There were even rumours that the Queen’s speech, also recorded on vellum, was being considered for transfer to a computer screen or autocue.

Yet despite being previously approved by the House of Lords, MPs rejected the proposal.

Labour’s Brian White MP led the opposition. Cynics could argue that with the only UK firm still producing vellum in his constituency, he had a vested interest in defeating this proposal.

However, as a former computer systems analyst he acknowledged that there was a place for modern technology to record acts of parliament, but not as a replacement for traditional vellum.

Perhaps it is with good reason that the paperless office promised by the digital revolution has yet to materialise.

Digital archiving seems set to remain a supplement rather than a substitute for paper-held records for a while yet.

Article from http://news.bbc.co.uk/